It seems tabletop role playing games always have some device to create chance outcomes, and in particular dice are convenient, portable, and often personalized devices for such occasions. But we might ask why we use them at all given that there are plenty of games with no dice (e.g. chess). Well, we have our reasons, which we’ll save to the end, but the generally agreed up on reason is probabilistic outcomes are fair and can be compared across characters and obstacles so that players know precisely how difficult an imaginary task is or how rare an outcome can be. But first, some notation.

What does 3d6 mean?

Considering sources, it’s surprising that the Advanced Dungeons and Dragons  (AD&D) 1st Edition (1E) Player’s Handbook does not contain a description of the so-called “d” notation, even though the notation is used throughout the book. For this edition, it first appears in the Dungeon Master’s Guide (DMG), which means players would have to work with a Dungeon Master or have that book to clearly understand what was going on. Fortunately, we learned D&D from the Moldvay Basic Set, pictured left, from 1977, which explains the notation thusly:

(AD&D) 1st Edition (1E) Player’s Handbook does not contain a description of the so-called “d” notation, even though the notation is used throughout the book. For this edition, it first appears in the Dungeon Master’s Guide (DMG), which means players would have to work with a Dungeon Master or have that book to clearly understand what was going on. Fortunately, we learned D&D from the Moldvay Basic Set, pictured left, from 1977, which explains the notation thusly:

“We often use abbreviations for the kinds of dice: a “d,” followed by the number of faces. For example: d8 means an eight sided die.

…

Whenever a number appears before the “d,” it means the number of times you need to roll the die. So “2d4” means “roll a four-sided die twice, and add the results,” for a total of 2-8. Or, if you have more than one set of dice, you can just roll two 4-sided dice at once, adding the results normally.”— Dungeons & Dragons: Players Manual (Red Box Edition), pg 12

A similar explanation is used in the AD&D 1E Dungeon Master’s Guide (DMG), but it goes on to explain the maths.

3d6 produces a normal probability distribution

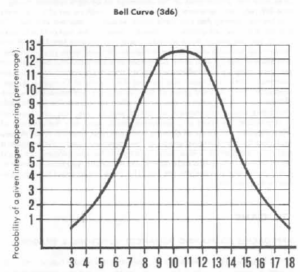

The purpose of the dice in early gaming was to simulate probability in a variety of ways. The simple 1d20 (see the notation above) produces a flat linear distribution, meaning any side of the die has an equal chance of appearing after a roll as any other. This is okay when all we really want is a random number generator, but as the AD&D 1E DMG explains, adding the results of multiple dice together produces a probability distribution where the middle values are much more likely than the minimum and maximum values. This produces a bell curve distribution (students of statistics will readily recognize the figure on the right, taken directly from the DMG) when rolling a character’s base statistics using 3d6, so the most likely outcomes are 10 or 11 while rolling a 3 or 18 are very rare.

The point of all of this is that any character would have a good chance of average stats, which in a simulated war game meant a group of a dozen characters would have a few outliers in both exceptional and poor statistics, but overall they would tend towards the average and be fair when deployed to the table for combat against any other fairly generated group of characters or monsters.

The curse of “roll” playing games

As we play these simulations more and more, the process of creating characters becomes impersonal. The story still might be heroic, but the mechanics are notoriously predictable. Many of us rolled a dozen characters for starting modules like B2: Keep on the Borderlands because they died so often – we stopped thinking of them as personal creations and more like roles we played for a time, ready to let go and re-roll when they perished. In some Old-School Renaissance (OSR) games, this is taken to an extreme called the Gauntlet, where players make 20 or more level 0 characters and run them through a set of battles designed to kill most of them. Those that survive, this being a simulation of probabilistic outcomes by design, become the level 1 characters that the players play throughout the rest of the campaign. In both cases, the players are rewarded for understanding the mechanics and probability (“roll” playing), rather than their improvisational or method-acting skills (roleplaying).

This is fine if you enjoy mathematical simulations (we certainly do) but there are many players who don’t, even to the point of playing exclusively “storytelling” games like Vampire: the Masquerade or Fate Core where the mechanics really exist when the dramatic or storytelling stakes are high. Make no mistake, in either style combat is a high-stakes aspect of the game where rolls determine a character’s continued existence, but in “roll” playing games it’s not personal while in “storytelling” games it very much is.

Some remedies, historic and current

One of the common methods of making a roleplaying game more intense is to forgo rolls for things where the stakes are low. For example:

- In D&D 3rd Edition, a player could “take 20” if they had unlimited time for a task and there was no penalty for failure, ensuring success

- In Pathfinder, players are instructed to roll only when failure would have consequences

- In Hackmaster and GURPS Fantasy, players do not roll initiative to determine who acts first, as the order of actions is always known by specific scores, even to the point of players seating themselves around the table in ascending initiative order for convenience

These small changes allow us skip the boring stuff – we don’t need to roll for a walk in the woods or to purchase a sword from a vendor. These things aren’t interesting parts of the heroes’ stories, so skip them. However, it doesn’t quite increase the tension the way rolls do when a vampire is trying to avoid a hunger frenzy in presence of their bleeding child in Vampire: the Masquerade or trying not to flee or cower in terror when facing the crawling chaos of a cosmic horror in Call of Cthulu, mostly because the fantasy games above are trying to reproduce a fantasy experience; the characters are courageous, daring, and larger-than-life, so charging an undead horde in single combat is assumed to be a normal part of their story. However, this might make for a less dramatic game as we fall into the habit of making rolls rather than making decisions that impact the story.

And here is where we conclude with what we think the dice should be for, which is to increase dramatic tension. When players make decisions that are risky and the outcome isn’t known, a roll of the dice makes the hand of fate appear by chance. The decisions to use one tactic over another according to the character’s talents, their desperation or foolishness, and the principles by which they live makes these decisions meaningful. There isn’t much drama in rolling up a character, as you can do it as many times as you like, so we favor systems where players decide what their characters are good at and what they are not, and which flaws (for there should always be some) they want to appear in the game as it plays. The Guantlet is an unnecessary slog that could be replaced with a random death generator.

In principle, we agree that boring things should take up as little time as possible, but we might even go further and let a game system make certain assumptions, such as 20 points allocated across skills however the player chooses, that can replace boring decisions with meaningful ones. The dice are for dramatic tension, so don’t even need to appear when roleplaying, characterization, and non-mathematical mechanics suffice. We expect this to make the game flow more easily to get to the dramatic opportunities quickly and with some consistency. Few people want to spend time rolling while listening at every door, so just give the players information if it matters. Some doors matter, but most are simply thresholds to more interesting things.